Sanzio Raphael

An Allegory

$540.00

Crocefissioneraffaello

$540.00

Les Trois Graces

$540.00

Mackintosh Madonna

$480.00

Madonna Sixtina

$540.00

Madonna With The Fish

$480.00

Pala Baglioni, Deposizione

$600.00

The Cardinal

$480.00

The Holy Family With A Lamb

$480.00

The Parnassus

$540.00

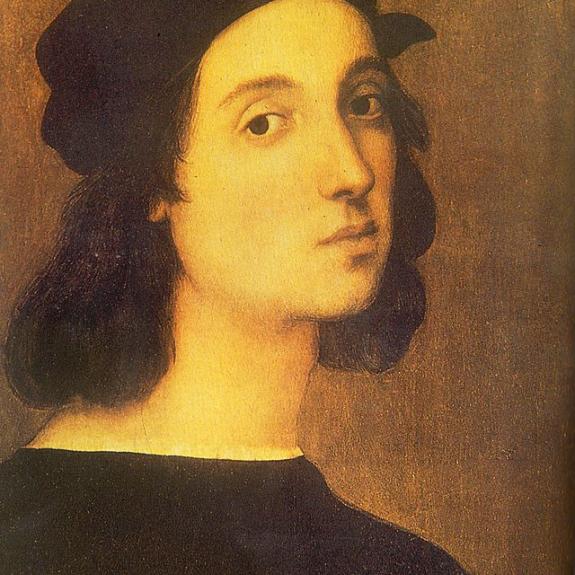

Sanzio Raphael

Sanzio Raphael (1483-1520)

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (March 28 or April 6, 1483 – April 6, 1520), known as Raphael , was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, he forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period.

Raphael was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop and, despite his death at 37, leaving a large body of work. Many of his works are found in the Vatican Palace, where the frescoed Raphael Rooms were the central, and the largest, work of his career. The best known work is The School of Athens in the Vatican Stanza della Segnatura. After his early years in Rome, much of his work was executed by his workshop from his drawings, with considerable loss of quality. He was extremely influential in his lifetime, though outside Rome his work was mostly known from his collaborative printmaking.

After his death, the influence of his great rival Michelangelo was more widespread until the 18th and 19th centuries, when Raphael's more serene and harmonious qualities were again regarded as the highest models. His career falls naturally into three phases and three styles, first described by Giorgio Vasari: his early years in Umbria, then a period of about four years (1504–1508) absorbing the artistic traditions of Florence, followed by his last hectic and triumphant twelve years in Rome, working for two Popes and their close associates.

From 1517 until his death, Raphael lived in the Palazzo Caprini in the Borgo, in rather grand style in a palace designed by Bramante. He never married, but in 1514 became engaged to Maria Bibbiena, Cardinal Medici Bibbiena's niece; he seems to have been talked into this by his friend the Cardinal, and his lack of enthusiasm seems to be shown by the marriage not having taken place before she died in 1520. He is said to have had many affairs, but a permanent fixture in his life in Rome was "La Fornarina", Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker (fornaro) named Francesco Luti from Siena who lived at Via del Governo Vecchio. He was made a "Groom of the Chamber" of the Pope, which gave him status at court and an additional income, and also a knight of the Papal Order of the Golden Spur. Vasari claims he had toyed with the ambition of becoming a Cardinal, perhaps after some encouragement from Leo, which also may account for his delaying his marriage.

Raphael's premature death on Good Friday (April 6, 1520), which was possibly his 37th birthday, was due to unclear causes, with several possibilities raised by historians. Vasari also says that Raphael had also been born on a Good Friday, which in 1483 fell on March 28.

Whatever the cause, in his acute illness, which lasted fifteen days, Raphael was composed enough to confess his sins, receive the last rites, and to put his affairs in order. He dictated his will, in which he left sufficient funds for his mistress's care, entrusted to his loyal servant Baviera, and left most of his studio contents to Giulio Romano and Penni. At his request, Raphael was buried in the Pantheon.

His funeral was extremely grand, attended by large crowds. The inscription in his marble sarcophagus, an elegiac distich written by Pietro Bembo, reads: "Ille hic est Raffael, timuit quo sospite vinci, rerum magna parens et moriente mori", meaning: "Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was dying, feared herself to die."

Raphael was highly admired by his contemporaries, although his influence on artistic style in his own century was less than that of Michelangelo. Mannerism, beginning at the time of his death, and later the Baroque, took art "in a direction totally opposed" to Raphael's qualities; “with Raphael's death, classic art – the High Renaissance – subsided", as Walter Friedländer put it.

Vasari himself, despite his hero remaining Michelangelo, came to see his influence as harmful in some ways, and added passages to the second edition of the Lives expressing similar views.

Raphael's compositions were always admired and studied, and became the cornerstone of the training of the Academies of art. His period of greatest influence was from the late 17th to late 19th centuries, when his perfect decorum and balance were greatly admired. He was seen as the best model for the history painting, regarded as the highest in the hierarchy of genres. Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses praised his "simple, grave, and majestic dignity" and said he "stands in general foremost of the first [i.e., best] painters", especially for his frescoes (in which he included the "Raphael Cartoons"), whereas "Michael Angelo claims the next attention. He did not possess so many excellences as Raffaelle, but those he had were of the highest kind..."

Reynolds was less enthusiastic about Raphael's panel paintings, but the slight sentimentality of these made them enormously popular in the 19th century: "We have been familiar with them from childhood onwards, through a far greater mass of reproductions than any other artist in the world has ever had..." wrote Wölfflin, who was born in 1862, of Raphael's Madonnas.

In Germany, Raphael had an immense influence on religious art of the Nazarene movement and Düsseldorf school of painting in the 19th century. In contrast, in England the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood explicitly reacted against his influence (and that of his admirers such as Joshua Reynolds), seeking to return to styles that pre-dated what they saw as his baneful influence.

He was still seen by 20th-century critics like Bernard Berenson as the "most famous and most loved" master of the High Renaissance, but it would seem he has since been overtaken by Michelangelo and Leonardo in this respect.