Francisco De Zurbaran

Francisco De Zurbaran

Francisco De Zurbaran (1598-1664)

Francisco de Zurbarán ( 1598 - 1664 ) is a painter of the Spanish Golden Age . A contemporary and friend of Velazquez , Zurbarán distinguishes himself in religious paintings - where his art reveals great visual force and profound mysticism - and he becomes an emblematic artist of the Counter-Reformation . First very marked by Caravaggio , his austere and dark style evolves to be closer to the Italian Mannerist masters . His representations move away from Velázquez's realism and his compositions are lighter in more acidic tones.

Francisco de Zurbarán was baptized on November 7, 1598 in Fuente de Cantos ( Badajoz ) . Two other great painters of the Golden Age will be born soon after: Velasquez ( 1599 - 1660 ) and Alonzo Cano ( 1601 - 1667 ).

At the age of fourteen, Zurbarán was apprenticed to Seville , in the studio of painter Pedro Diaz de Villanueva (1564-1654), where Alonso Cano joined him in 1616 . His apprenticeship ends in 1617 , when he marries Maria Páez. He then lives in Llerena ( Extremadura ), where his children are born, Maria, Juan (who will become a painter and will die during the great plague of 1649) and Isabel Paula. After the death of his wife, he remarried around 1625 with Beatriz de Morales. We know that he is already known in 1622 , since, by contract, he undertakes to paint an altarpiece for a church in his hometown.

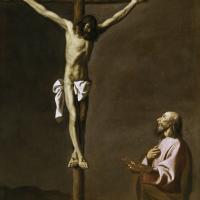

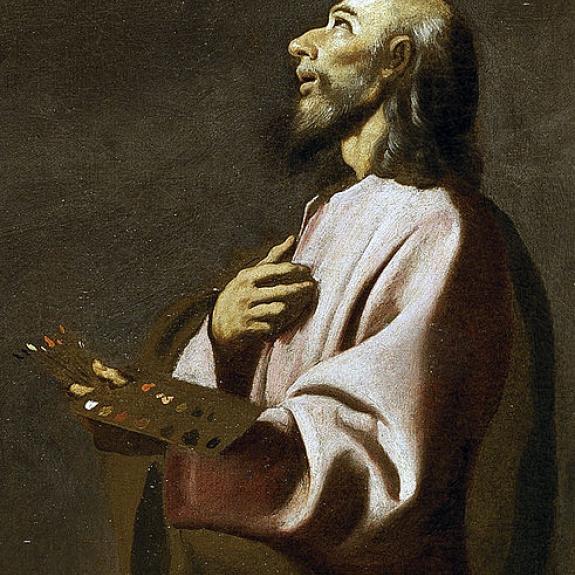

In 1626 , he signed a new contract with the community of the Friars Preachers of the Dominican Order of San Pablo de Real, in Seville , to execute twenty-one paintings in eight months. And it was in 1627 that he painted Christ on the cross , a work admired to such a degree by his contemporaries that the Seville City Council offered him to settle there in 1629 .

In this painting, the impression of relief is striking. The Christ is nailed to a cross in rough-hewn wood. The white, luminous linen that surrounds her waist, with her scholarly and already baroque drapery , contrasts dramatically with the flexible and well-formed muscles of the body. The thin face bends over the left shoulder. The suffering seems outdated and leaves room for a last dream of Resurrection , the last thought of a promised life whose body, no longer tortured but already glorious, is the sign.

As for Velasquez's Crucifixion (painted around 1630 , steeper and more symmetrical), the feet are here nailed separately. At that time, sometimes monumental works disputed representations of the Crucifixion and in particular the number of nails. For example the Revelations of Saint Brigitte , who spoke of four nails. Moreover, after the Tridentine decrees, the spirit of the Counter-Reformation opposes the great stagings and directs the artists towards representations of Christ alone. Finally, many theologians maintain that the body of Jesus and Mary could only be perfect. Zurbarán adopts these lessons, and asserts himself at twenty-nine as an indisputable master.

Zurbarán was famous before the age of thirty, mainly thanks to the cycle of the Merced Calzada , of which Alonzo Cano, master painter since 1626, had refused the order.

He remained very popular after his death, and his fame went well beyond the borders of Spain. The older brother of Napoleon , the unpopular Joseph Bonaparte , whom the Spaniards at best called "the intruder king" or at worst "Pepe botellas", had sent to Paris , for the Napoleon Museum, many of Zurbarán's major works. . Several generals of the Empire, and Marshal Soult , drew from the pictures collected at Seville after the closing of the convents of men.

But why Zurbarán? Rather than the greed of the new rich, can we not evoke "among men generally out of the people and without artistic culture, a spontaneous attraction to this simple painting, warm and direct, and that could awaken in some of the main lovers, Marshal Soult, General d'Armagnac, certain memories of their childhood Languedoc or Gascon "? (Paul Guinard, Treasures of Spanish Painting , Paris, Museum of Decorative Arts, 1963 ).

From 1835 to 1837, Louis-Philippe sent to Spain baron Isidore Taylor, Royal Commissioner of the French Theater, to collect a collection of works, dispersed thereafter. Represented by 121 numbers, Zurbarán was however less appreciated than Murillo. It was judged only from a romantic point of view , and we saw especially in him the "Spanish Caravaggio", painter of the monks. It was the Saint Francis on his knees with a skull which held the attention.

Zervos talks about the news of Zurbarán's painting. Indeed, if we look closely at the treatment of the garment of St. Andrew ( Budapest ), the mantle of St. Joseph ( The walk of St. Joseph and the Child Jesus , a masterpiece found in the church Saint-Médard in Paris), of the dress of Blessed Saint Cyril (Boston), one understands that some speak of a "desired stylization, the very premise of Cubist abstraction " (Catalog of the exhibition of 1988, p. 156 ). And the still life of the Disciples of Emmaus is not close, in its rigor, of the still life with the kettle of Cézanne (Museum of Orsay)?

Like all masters, Zurbarán does not give the feeling of being limited by the desire to conform to the expectations of the sponsors. The second-rate artists proclaim loudly and loudly that genius is based on freedom, and that to be free is to obey no one. Navrante definition of freedom that condemns in fact to be the servant of his desires , his passions , even his impulses . The false artist without genius , and who does not even have the courage of talent (which would require work) thinks that the public is obliged to kneel before the unbridled oozing of a hypertrophied self. To this must be opposed the genius of a Zurbarán whose real freedom is to transcend the constraints, the rules, without refusing them, and to turn any requirement into an opportunity to create a masterpiece. It is this ability to enslave the rules (which enslave only mediocre minds) within the framework of creation, which is also found in Jean Racine .

However, when you reach the peaks, there must be no question of hierarchy between the great artists. To "note" the geniuses, one would have to believe oneself superior to them! The best that we have to do is to meditate on the works, to try to understand the problems that arose to them and to reflect on the echo that their forms have found in the history of art. El Greco, Zurbarán, Velazquez, Murillo are not (or no longer) in competition: each in his own way has the look that we throw on art, but also on people, on things. Our world is built by the contemplation of works.

On this point, let Yves Bottineau (Inspector General of the Museums of France, in charge of the National Museum of the Palace of Versailles and Trianon):

Today, in accordance with a habitual balance in the history of the arts, some commentators, in private at least, willingly lower Zurbarán by comparison with the poetic ease of Murillo. But Spanish painting is so rich that the tribute paid to its greatest representatives must not take the form of a classification, subject to variations of taste and judgment; he must follow the path of enlightened and admiring prudence.