El Greco

Christ Clasping The Cross

$480.00

Portrait Of A Doctor

$480.00

Portrait of a Gentleman

$480.00

Portrait of A Young Nobleman

$480.00

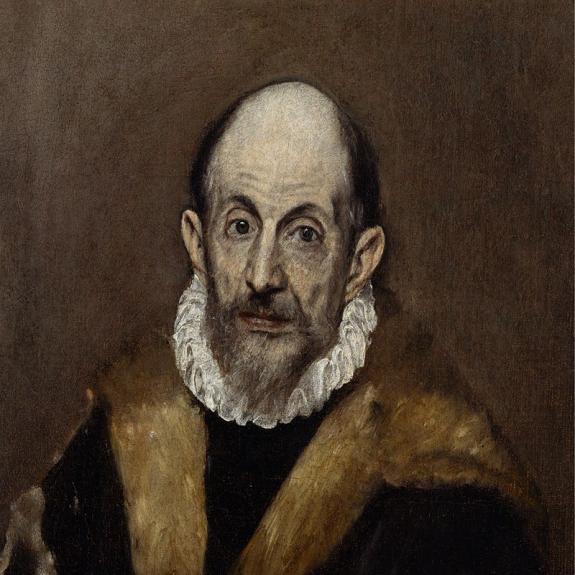

Portrait of an Ederly Man

$540.00

Portrait of Dominican Friar

$480.00

Saint Bartholomew

$480.00

Saint Benedict

$480.00

Saint James The Elder

$480.00

The Agony In The Garden

$480.00

The Entombment Of Christ

$540.00

The Holy Visage

$480.00

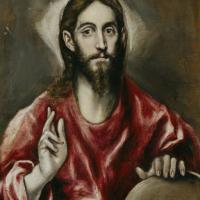

The Savior

$480.00

The Trinity

$480.00

El Greco

El Greco (1541-1614)

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (October 1541 – 7 April 1614), most widely known as El Greco ("The Greek"), was a painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. "El Greco" was a nickname, a reference to his Greek origin, and the artist normally signed his paintings with his full birth name in Greek letters, Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος, Doménikos Theotokópoulos, often adding the word Κρής Krēs, Cretan.

El Greco was born in the Kingdom of Candia, which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice, and the center of Post-Byzantine art. He trained and became a master within that tradition before traveling at age 26 to Venice, as other Greek artists had done. In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance taken from a number of great artists of the time, notably Tintoretto. In 1577, he moved to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best-known paintings.

El Greco's dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the 20th century. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism, while his personality and works were a source of inspiration for poets and writers such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis. El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school. He is best known for tortuously elongated figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantinetraditions with those of Western painting.

The primacy of imagination and intuition over the subjective character of creation was a fundamental principle of El Greco's style. El Greco discarded classicist criteria such as measure and proportion. He believed that grace is the supreme quest of art, but the painter achieves grace only if he manages to solve the most complex problems with obvious ease.

El Greco regarded color as the most important and the most ungovernable element of painting, and declared that color had primacy over form. Francisco Pacheco, a painter and theoretician who visited El Greco in 1611, wrote that the painter liked "the colors crude and unmixed in great blots as a boastful display of his dexterity" and that "he believed in constant repainting and retouching in order to make the broad masses tell flat as in nature".

Art historian Max Dvořák was the first scholar to connect El Greco's art with Mannerism and Antinaturalism. Modern scholars characterize El Greco's theory as "typically Mannerist" and pinpoint its sources in the Neoplatonism of the Renaissance. Jonathan Brown believes that El Greco endeavored to create a sophisticated form of art; according to Nicholas Penny"once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his own—one that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting".

In his mature works El Greco demonstrated a characteristic tendency to dramatize rather than to describe. The strong spiritual emotion transfers from painting directly to the audience. According to Pacheco, El Greco's perturbed, violent and at times seemingly careless-in-execution art was due to a studied effort to acquire a freedom of style. El Greco's preference for exceptionally tall and slender figures and elongated compositions, which served both his expressive purposes and aesthetic principles, led him to disregard the laws of nature and elongate his compositions to ever greater extents, particularly when they were destined for altarpieces. The anatomy of the human body becomes even more otherworldly in El Greco's mature works; for The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception El Greco asked to lengthen the altarpiece itself by another 1.5 feet (0.46 m) "because in this way the form will be perfect and not reduced, which is the worst thing that can happen to a figure'". A significant innovation of El Greco's mature works is the interweaving between form and space; a reciprocal relationship is developed between the two which completely unifies the painting surface. This interweaving would re-emerge three centuries later in the works of Cézanne and Picasso.

Another characteristic of El Greco's mature style is the use of light. As Jonathan Brown notes, "each figure seems to carry its own light within or reflects the light that emanates from an unseen source". Fernando Marias and Agustín Bustamante García, the scholars who transcribed El Greco's handwritten notes, connect the power that the painter gives to light with the ideas underlying Christian Neo-Platonism.

Modern scholarly research emphasizes the importance of Toledo for the complete development of El Greco's mature style and stresses the painter's ability to adjust his style in accordance with his surroundings. Harold Wethey asserts that "although Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, the artist became so immersed in the religious environment of Spain that he became the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism". He believes that in El Greco's mature works "the devotional intensity of mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the period of the Counter-Reformation".

El Greco also excelled as a portraitist, able not only to record a sitter's features but also to convey their character. His portraits are fewer in number than his religious paintings, but are of equally high quality. Wethey says that "by such simple means, the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank as a portraitist, along with Titian and Rembrandt".

El Greco painted many of his paintings on fine canvas and employed a viscous oil medium. He painted with the usual pigments of his period such as azurite, lead-tin-yellow, vermilion, madder lake, ochres and red le